It’s shadow boxing so far, the so-called debate over science of rhGH testing for pro athletes in America, as opponents shout from across the mat.

It’s shadow boxing so far, the so-called debate over science of rhGH testing for pro athletes in America, as opponents shout from across the mat.

Staying put in one corner, the anti-doping agencies claim they stand on sound science in their current Olympic blood test for recombinant human growth hormone.

Posturing in the other corner, pro baseball and football claim they demand sound science for serum analysis of athletes.

But real action isn’t happening. Both sides just lob trash talk, through media, over the controversial isoform scan for rhGH.

No one appears ready to enter the ring for public discussion on the science involved—or lacking—with the mysterious WADA system that only recently produced a first announced positive result on an athlete, after 1,500 tests since 2004.

No one wants to budge yet, not WADA and USADA, not management of the NFL and MLB, nor the two player unions.

None has accepted a prime opportunity for open forum, even at the behest of esteemed American testing engineer Dr. Don H. Catlin, president and CEO of the nonprofit Anti-doping Research laboratory in Los Angeles.

“We now have reached a critical juncture,” Catlin wrote in a March 28 statement on the ADR site. “I invite sports organizations and unions, anti-doping agencies and other science experts to set a meeting to discuss the issues related to hGH testing.” A Reuters news report also circulated, outlining Catlin’s proposal.

But a week later, Catlin still hasn’t heard from pro sports or anti-doping agencies. “Not a peep,” he wrote in an email Sunday.

Catlin already knew his idea is a long shot. During a March 19 telephone interview, he acknowledged several barriers to staging open summit on GH testing replete with experts of independent science, beyond those employed in sports and anti-doping who comprised the recent Partnership for Clean Competition conference in New York.

The foremost challenge for any progress is overcoming the varying political agendas of parties involved. “Where’s the impartiality? I don’t see any here,” Catlin charged, labeling the self-hype of PCC members as a research consortium to be “disingenuous.”

WADA and USADA conflict with American athlete unions in particular, having exchanged criticism and insults through news media for years. “The titans in this field don’t sit down; they just throw stones at each other,” said Catlin, who’s worked with the combating groups during his testing career spanning three decades.

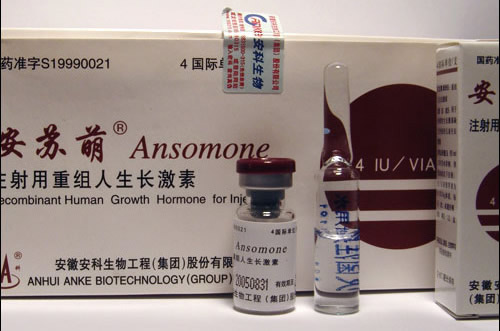

Anti-doping officials allege leagues and unions resist blood testing because too many athletes would be caught for using illicit growth hormone, and undoubtedly a problem exists with use and abuse of the drug in sport. Extensive evidence surrounds American football and baseball, including historical allegations, documented users, no prevention, and increasing accessibility and cultural acceptance of rhGH, for people of every age and vocation.

Union representatives counter-attack WADA, declaring the indirect scan for GH isomers is unreliable and lacks scientific validation, given its measly 24-hour detection window and the agency’s suspicious withholding of clinical trial data. Indeed, Catlin qualified the isoform as “simply not a useful test” while beseeching anti-doping officials to release the critical numbers in question.

Catlin contends the WADA-USADA mission for seeing U.S. pro sports adopt rhGH testing cannot advance within the polarized state of anti-doping business. “I don’t see any scientific discussion. There are people in WADA who know a fair amount about it. Who can tell you exactly why it took so long to get the (isoform) ratio figured out. That’s something that the baseball people would like to know.”

Unions are typically cast as resistant villains in disputes over anti-doping, but Catlin doesn’t buy that regarding GH testing. “The unions are decent people; they do actually care about their athletes,” he said. “The unions are very strong, they’re very powerful, but they’re not stupid people. I think they can be reasoned with, but you don’t have a dialogue. Where’s the dialogue? Where’s the discussion? Why are the major players not at the table?”

“I think both sides are at fault,” Catlin concluded. “Both sides don’t want to get too close to this, because they would have to reveal something. And the [isoform] test might not look so well.”

Meanwhile, in London, England, GH-testing pioneer Dr. Peter H. Sonksen hasn’t heard from American pro sports about his research team’s long-standing biomarker blood test for rhGH.

“No—never met them,” Sonksen stated of U.S. sport officials, in an email Sunday.

But pro sports know about his team and test, which WADA has inexplicably sidelined for 10 years, according to comments in a March 29 report of The New York Times that failed to mention Sonksen.

In addition, football insiders say the NFL players union is reviewing the biomarker system, after a March 21 report on this blog unleashed harsh criticism of the WADA isoform leveled by Catlin, Sonksen and American doping expert Dr. Charles E. Yesalis.

Sonksen says his testing system—which builds bio-profiles of athletes for “outcome” substances of GH in the bloodstream, such as IGF-1 and collagens—could immediately impact pervasive use of recombinant growth hormone in an American sport like the NFL, with 1,700 athletes among 32 franchises located in major metropolitan areas. He sees the key factor as “the logistics of collecting samples and transporting” to WADA-approved labs, which number two in the United States. Total cost hasn’t been calculated but wouldn’t exceed NFL urine testing for anabolic steroids already in place, according to Sonksen.

“WADA-USADA would have to approve the test, and this would involve training and implementation of the methods in the laboratories. This will take some time,” said Sonksen, who, funded by the anti-doping agencies, continues laboratory work as visiting professor at the University of Southampton Medical School.

Finally, Sonksen believes, the anti-doping politics are aligning for deployment of the peer-reviewed biomarker test, with its reputed detection window of 10 to 14 days—and in time for assisting the beleaguered isoform at the 2012 London Olympics. “The two tests are useful together,” Sonksen said in a March 17 interview by webcam. “The isoform test is only useful for out-of-competition (sampling), and our test works out of competition and in competition.”

Sonksen has fought WADA and IOC officials for decades, whom he calls “sports politicians… not scientists.” But now he boasts allies for his test and team in administrators of WADA’s British arm. “It’s only recently, I think, since we’ve teamed up with UK Sport—or the UK Anti-Doping fraternity, as they are now—that (WADA wants) to have the test up and running for the London Olympics. There’s more pressure on (WADA) from the political front.”

Michael Stow, UKAD spokesman, confirmed agency confidence in the biomarker system. “UK Anti-Doping (representatives) have been working with the team in Southampton that includes Prof. Sonksen since 2006,” Stow wrote in an email. “We have been working hard and are very keen to see this test accredited for use by anti-doping agencies worldwide.”

Sonksen says his team invites open discussion of their biomarker test with whomever, anytime and anywhere. He personally invites calls and email, including from the NFL, MLB, WADA and USADA, independent scientists, and the American press.

“We’d be quite happy for that,” he said. “We’ve published all our papers in peer-reviewed journals. And I think peer-reviewed medical journals are about as secure science as you can get. … We still have papers to come. We’re still writing them.”

Sonksen, a former rugby player, is a cheery man at age 73. But he remains scornful of many anti-doping officials for their disregard of scientific convention, open critique. “I’m more forthright because I’m older and have been dealing with the politics of the IOC and WADA for nearly 20 years,” he wrote Sunday. “You’ll get a straight answer from any of our team. We all believe in (quote) ‘transparency.’ ”

Matt Chaney is a journalist, editor, teacher and publisher in Missouri, USA. E-mail him at mattchaney@fourwallspublishing.com. For more information, including about his 2009 book Spiral of Denial: Muscle Doping in American Football, visit the home page at www.fourwallspublishing.com.